Moods of Norway

Early on during the second season of "Mad Men," there is a confrontation in a stable between Betty Draper and a younger man. As Betty readies herself to head home, the man begins unloading all of his anxieties regarding his upcoming marriage. Then, this being "Mad Men," he makes a move on her, which she quickly shuts down. Undeterred, he crosses the stable.

"You're so profoundly sad," he says.

Cold as ice.

"No," she says. "It's just my people are Nordic."

Nordic people (Scandinavians, specifically) have long had a reputation among foreigners as cold, rude, or, as with Mrs. Draper, sad[1], and it was this conception of Scandinavians I had in mind when Dom and I landed in Oslo one sunny morning early last month. It’s risky, of course, to put an entire peoples into a single box, especially when your judgment is based only on second and third hand accounts. So during our stay, I sought to find the truth of these characterizations. Are Norwegians really rude? Are they cold? Or, more plausibly, are they simply misunderstood?

The first Norwegian we spoke to was a man in the airport. He worked for Flybussen, an express bus service. He was older, with greying hair and glasses, and he stood behind the counter staring at us with probing eyes as we approached. He was helpful, but unsmiling, efficiently answering as we asked if the bus went downtown (yes), where to catch it (outside), how much tickets were (expensive), and if we could buy them from him (no). He then pointed us to where the bus would be and continued about his business.

I came away from the booth with a weird feeling. The man hadn't been rude, per se, but he wasn’t exactly a paragon of customer service. It felt as though he was just barely masking his contempt for us. Then again, I was tired and hungry, so maybe, I thought, it was just me. Besides, I’ve worked in customer service, I know the tedium that can accompany answering dumb questions from dumb customers hour after hour, day after day.

In an act of characteristic generosity, I decided that this one experience wouldn’t be enough on which to base my judgement of the rest of the population. Yet, the more time we spent in the country, the more it became evident that the strange vibe I got from the man couldn't wholly be attributed to his disdain for his job, nor to my empty stomach. Every person we met kept an eerie emotional distance, their faces never straying far from a baseline of impassivity. This often led to confusion, and, at its worst, feelings of unease.

“Oh, yes, Norwegians are very repressed,” our Italian Airbnb host confirmed. He had lived in the country for a number of years, recently in Stavanger, where we stayed with him. Prior to that he was in Trondheim, about a thirteen hour drive north.

“Until they get drunk,” he continued, smirking. “Then their inner viking comes out.”

We had noticed. Our room overlooked Øvre Holmegate, nicknamed "Fargegata," or “The Colourful Street”, for the buildings painted in bright colours that line either side. It's narrow, paved with cobblestones, and home to quiet shops and cozy cafés during by day. But come sundown, the cafés turn into bars. Then, finally, can you see the straight-faced locals let loose.

The idea that Norwegians have to be drunk to express any emotion is the joke behind the cover of The Social Guidebook to Norway, a tongue-in-cheek book describing and explaining the peculiar habits of Norwegians. Its author, Julien S. Bourrelle (a Canadian, as it happens) has become something of an authority on Scandinavian customs, and in 2013 he founded MONDÅ, an organization that aids foreigners in adapting to Scandinavian society. He can be seen on YouTube at events such as TEDx speaking to audiences in Norway and Sweden on the subject. Images from the book are projected on screens behind him, often eliciting knowing chuckles from the audience.

The tendency to conceal one's emotions can explain Betty Draper appears sad, or why a stone-faced Norwegian might give someone like me the creeps. Humans rely on facial expressions to gauge the thoughts and feelings of others. A blank face leaves you guessing, and in the context of being a dumb tourist or maladapted foreigner, is more likely to be interpreted as annoyance or condescension.

I've had people misread me on account of my own tendency to not smile, a trait that, along with an argumentative temperament and an unnecessary amount of body hair, I inherited from my father. Thus, as the trip progressed, I began to identify with the locals to a certain degree. Granted, my “resting bitch face” usually only surfaces when I’m particularly focused on something. In the course of normal conversation I can usually express myself reasonably well.

Typical small talk.

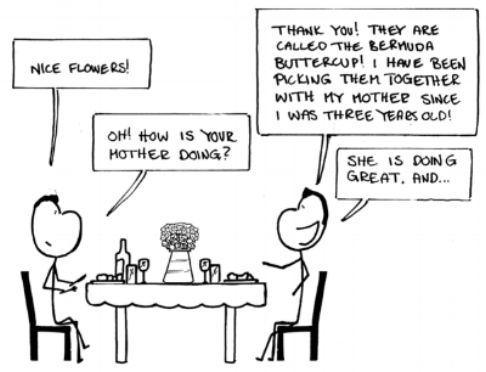

Conversation—that’s another thing Norwegians seem to struggle with, and it's a further issue taken up in the Guidebook. The scene is a dinner table. In the first drawing, two people exchange small talk about some flowers on the table[2]. Next, we see two Norwegians having a decidedly briefer version of the conversation. In much of world, we conclude, friendly banter is a normal and expected part of interaction with strangers; in Norway, not so much.

Then again, I’ve never been much of a talker myself. As a child I was shy, but now it’s more of a conscious effort. As I mentioned, I can get argumentative. So I keep my mouth shut to stop me from saying the wrong thing and alienating or offending someone I care about. Yet I'm still able to engage in friendly chit-chat with a stranger. Perhaps the Norwegian can, too. Can, but won’t.

This pair has fewer flowers and no tablecloth, maybe a nod to the minimalism of Scandinavian design. They're also down a bottle of wine, so maybe they would talk more if they would just loosen up a bit.

It’s possible that the Norwegians we met weren’t comfortable speaking with us in English. (Although, it must be said that everyone we spoke to seemed to have an impressively strong grasp of the language.) But Bourrelle's point is that Norwegians just don't care for small talk. For one thing, he says, socialization takes place in a more contextualized manner; it’s not something that just happens out of the blue. Furthermore, politeness is seen to be more about not bothering people than engaging with them. This isn't without it's up-sides. In Bermuda, you have to say “good morning"to everyone before you can get anything done. In Norway, you just do it.

In 1933, "En flykting krysser sitt spor" ("A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks") by Dano-Norwegian writer Aksel Sandemose was published. In it, Sandemose describes a fictional town, Jante, and the code its inhabitants live by: Janteloven, or the Law of Jante. Janteloven (summed up as "you’re not special, so don’t think you are") has been read as an exaggerated version of a real but implicit social law that exists throughout Scandinavia. It manifests through attitudes that value modesty over pride; conformity over difference. Janteloven might also explain, then, a Norwegian’s aversion to conversation: Why would anyone care what I think?

As we were ending our stay in Norway, I was growing to appreciate the up-sides of Janteloven. It was around 4:30a.m. as we walked to the bus terminal, and a light rain laid like a blanket over the city. We boarded the Flybussen to the Stavanger Aiport, and had only been on board for a few minutes before it stopped at a hotel to pick up a lone passenger. He got on and took a seat across the aisle from us. As soon as he sat down he took out his phone, and for the duration of the trip he held the entire bus hostage to his conversation.

He mostly complained about different people and things, ending each rant with an exasperated “Oh, fuck off." Occasionally he swapped that out for a drawn out “Oh my Gooooooood…” He was English and a flight attendant, and he sounded like a cheap Ricky Gervais impression. He was a living caricature. At one point, he changed from airline talk to his personal life, describing the time his former fuck-buddy had tried to fist him. Oh, fuck off. It was a lot to take in that early in the morning (the story, I mean), and by the time we had reached the airport Dom and I had gone from frustrated, to angry, to incredulous, to amazed. As we pulled into the airport he was talking about his plans for an upcoming trip to Japan.

“I’m just going to eat, eat, eat, eat, eat!” he said into the phone.

“That’s just what you do there.”

[1] I'll note that this also provides Matthew Weiner an easy out for January Jones' stilted performance in the early seasons of the show.

[2] Funny that they're Bermuda Buttercups. I had never heard of them before finding this panel, and at first I thought they were just some esoteric sounding perennial that Bourrelle had made up. Turns out they're a type of sorrel. I don't think I've ever seen them in Bermuda, but I do have fond memories of the childhood novelty of biting into what must be some other type of pink or purple-flowered sorrel, judging by the pictures. Good acidity.